Pearl of the Orient Reconstructed

How Great Power Politics Shaped Hong Kong’s Sovereignty

At first glance, orthodox narratives of Hong Kong’s past seem bipolar. Pro-British perspectives tend to reject the idea that the territory had any meaningful history at all before the Opium Wars and emphasize the colonial system’s contribution in transforming a “barren island” into a global metropolis, whereas pro-Chinese perspectives tend to exaggerate anti-colonial sentiments and depict China as a victim of Western imperialism. For all their differences, however, both views diminish the role of Hong Kongers as a distinct community fostered over more than 150 years. Nowhere is this more obvious than on the issue of sovereignty: Neither Beijing nor London are willing to interpret the 1997 handover as anything but an inevitable “reunion with the motherland.” If history writing indeed epitomizes existing power relations, perhaps the deliberate neglect mirrors my argument that their legitimate right of self-determination, as a non-self-governing people, was blatantly disregarded by the international community’s indifference.

Despite its small size, Hong Kong was unique as a British colony adjacent to Red China and therefore played a significant role — both regionally and globally — in the period between the Korean War and the Tiananmen Massacre. By the 1950s, more than a century since its colonization, Hong Kong was one of the most spine-tingling places in Asia to catch a glimpse of Cold War maneuvers. There the Americans were operating their single largest consulate, while both Communist and Kuomintang operatives were fighting their finished Chinese Civil War, as exemplified by the Kashmir Princess incident of 1955 and the Double Tenth Riots of 1956. Understandably, great powers — not just China and Britain but also the United States and the Soviet Union — all had strong interests in Hong Kong, on which they exerted their influence in order to advance their respective agendas, often beyond Hong Kongers’ control or even knowledge.

These instances abound. In response to the Soviet Union’s successful launching of Sputnik 1 in 1957, Dwight D. Eisenhower, hoping to renew America’s “special relationship” with Britain, made a deal to defend Hong Kong with nuclear weapons in exchange for Harold Macmillan to help block Beijing’s U.N. entry and to forgo his earlier earlier contemplation to surrender the colony. And in 1962, when Mao Zedong blasted his counterpart Nikita Khrushchev for Soviet weakness in the Cuban Missile Crisis, Moscow hit back by ridiculing Chinese hypocrisy for tolerating Hong Kong as an imperialist haven. The back-and-forth continued throughout the 1960s. Once China was finally admitted to the U.N. in 1971, it requested the removal of Hong Kong from the official List of Non-Self-Governing Territories within four months to deter its potential independence under U.N. auspices. Regardless of the ongoing Sino-Soviet split, Leonid Brezhnev’s Kremlin — keen to suppress capitalism in the communist sphere of influence — endorsed the Chinese position on ideological grounds with the support of Beijing-friendly Third World nations in Africa.

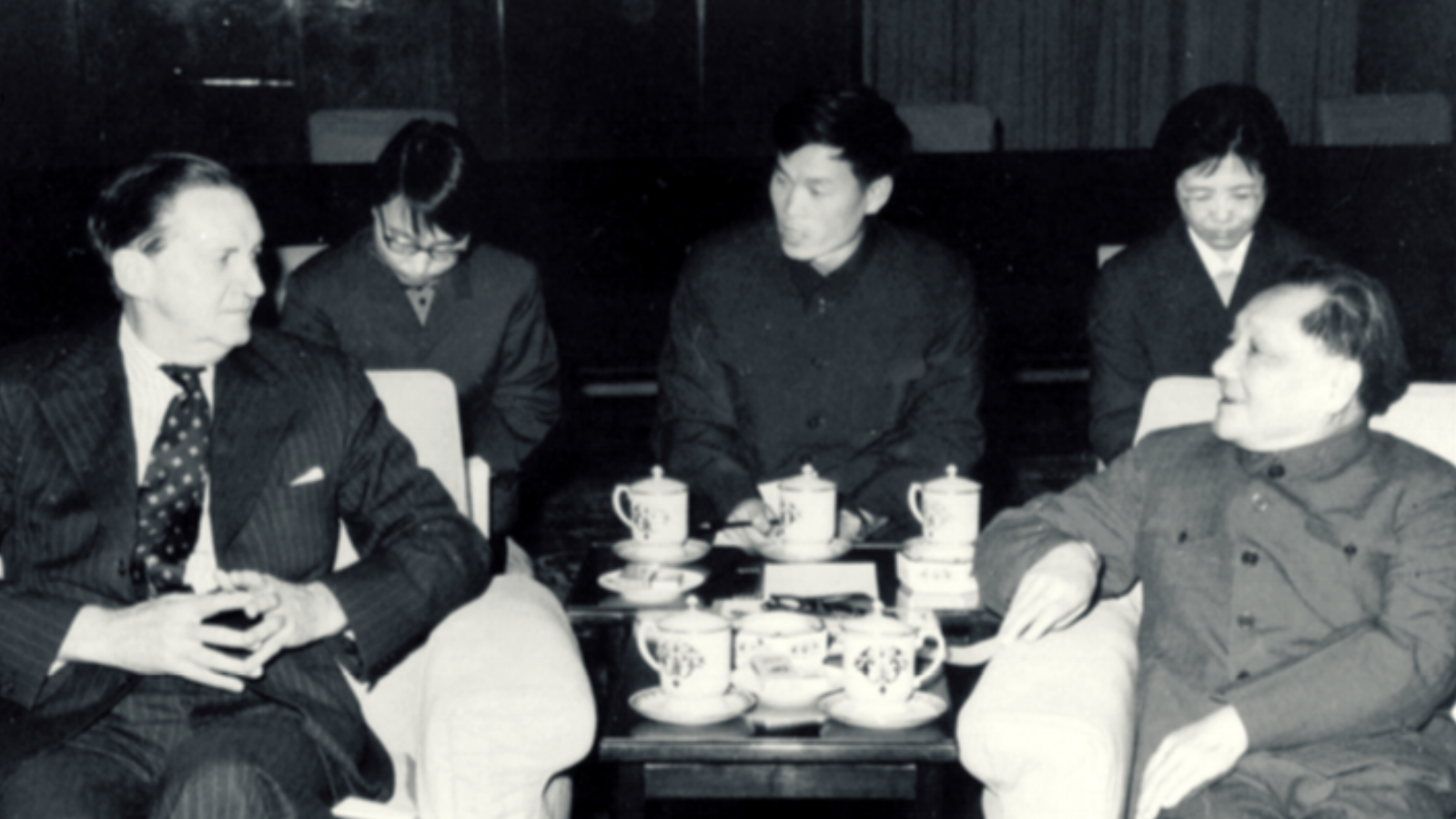

Governor Murray MacLehose’s signaled London’s intention to keep hold of Hong Kong beyond 1997 — when the 99-year lease of the New Territories signed between the British and Qing Empires was set to expire — during his historic meeting in 1979 with Deng Xiaoping, who didn’t give a clear answer. As part of his strategy for Greater Chinese unification, the new Chinese paramount leader later came up with “One Country, Two Systems” to lure Taiwan, but, having been met with apathy, adapted it for Hong Kong instead. Meanwhile, Margaret Thatcher was convinced she had the military might to defend distant colonial outposts after a decisive victory in the Falklands War of 1982. But China was no Argentina. Overconfident yet underprepared, the Iron Lady soon lost the upper hand to the Chinese in the negotiation on Hong Kong. These talks continued over the next years behind closed doors until the signing of the Sino-British Joint Declaration in 1984. Not only were Hong Kongers kept out of the entire process, the subsequent Basic Law Drafting Committee to write the territory’s future constitution was also appointed by Beijing. By the time the international community began to worry about Hong Kong after 1989, everything was too late: The handover was now just eight short years away.

Advised by Jane Burbank, this project was submitted to New York University in September 2017 as my M.A. thesis. In total, I’ve relied on a wide array of primary sources online and from five archival collections across three continents. Preliminary research was conducted during my Hong Kong visit in the summer of 2016 and then throughout the fall at my home institution’s Bobst Library United Nations and International Documents Collection. As part of my work with the Decoding Hong Kong’s History public history project, I traveled twice to London — in February and March 2017 — for British documents. Finally, a small grant from the Draper Interdisciplinary’s Master Program funded my trip to Los Angeles in July 2017 for U.S. files stored at the Richard Nixon and Ronald Reagan Presidential Libraries and Museums. My department selected this work as winner of the Rose and Herbert H. Hirschhorn Thesis Award and nominated it for the graduate school-wide Master’s Award for Academic Achievement in the Humanities.

![[2.3] Bandung.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ad9026150a54fcfca6cd749/1524955506282-TYGEK4G3GE0VATB0NUIP/%5B2.3%5D+Bandung.jpg)

![[3.1] Eisenhower-Macmillan.jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ad9026150a54fcfca6cd749/1524955077923-WOSDMDOPKN37GO169PP7/%5B3.1%5D+Eisenhower-Macmillan.jpg)

![[5.1] Bush U.N..jpg](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/5ad9026150a54fcfca6cd749/1525116462526-H9B86AF6COE7AGNS88QH/%5B5.1%5D+Bush+U.N..jpg)